Doing Business the Canadian Way: Canada’s Struggle with Modern Slavery Legislation

Countries in the OECD and beyond have taken up the cause of creating a rigorous mandate for addressing modern slavery. With S-211, Canada and its business community have an opportunity to learn from previous legislative efforts. Will Canada avoid the pitfalls of first generation modern slavery laws to develop a robust standard and benchmark that offers meaningful human rights due diligence and effective access to remedy for workers?

As the Canadian Government strives to ensure that Canadian entities are ‘Doing Business the Canadian Way’ in the extractive sector, it is estimated that an eye-watering $34bn worth of goods potentially associated with forced or child labor are imported into Canada every year. Over the last 21 months, Canada has made just one seizure in October 2021 of forced labor-made goods. In contrast, US customs officials have intercepted 1,469 shipments of goods related to forced labor in the fiscal year of 2021 alone.

The implications aren’t lost on observers; supply chain human rights experts and Director of Public Policy at Simon Fraser University, Professor Genevieve LeBaron has argued that Canada is “becoming a dumping ground for goods that have been rejected by the U.S. and other countries.”

The Government’s confrontation with modern slavery hit the headlines again with the publicized cancellation of contracts with medical glove manufacturer Supermax worth $220m in January 2022 due to allegations of debt-slavery and inhumane working conditions at their Malaysian factories.

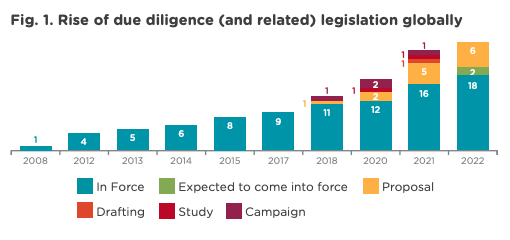

The UK, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, the EU, and parts of the US, have already passed modern slavery legislation. Although Canada has tabled four pieces of legislation with similar parameters on modern slavery and forced labour, thus far the country’s Parliament has failed to pass any into law.

Source: QIMA – Mandatory Human Rights & Due Diligence: How to Get Prepared

Canada Fights Back with Bill S-211

Canada’s Minister of International Trade, the Honourable Mary Ng, recently re-affirmed the country’s commitment to the modernization of international trade rules — including the ending of modern slavery — in a G7 joint statement.

Meanwhile, in another branch of government, the Canadian Supreme Court recently gave the go-ahead for Eritrean miners to take Nevsun, a Canadian company with mines in Eritrea, to court in Canada for alleged human rights abuses in the Bisha gold mine.

In response to these concerns and others, Canada’s Bill S-211, “Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains”, has been voted into committee by the Canadian Parliament. It signals a desire on the part of lawmakers to eradicate the stain of modern slavery from goods in Canadian shopping baskets and from Canadian business activities abroad.

The Bill expands the scope of Canada’s previous attempt at enacting modern slavery legislation, Bill S-216, to include government institutions, and represents a direct acknowledgement from the Canadian Government that supply chain due diligence can minimize human rights risks. The criteria also covers businesses that have at least $20m in assets; have generated $40m in revenue; or employ at least 250 employees on average.

Bill S-211 is the third of four legislative measures with an objective to deconstruct labor human rights abuses or modern slavery in both the Canadian Government and in Canadian companies. Although Canada has failed to pass any of its tabled legislative pieces on modern slavery thus far, the S-211 Bill has widespread political and public support, and is expected to pass quickly.

Global Precedence: Bill S-211 in Context

Though Canada is late to the game in passing modern slavery legislation, they stand to benefit by incorporating lessons learned from their international partners. So how does Bill S-211 stack up on the international stage?

Of its predecessors, Canada’s Bill S-211 most closely resembles the UK’s Modern Slavery Act of 2015 which, in the 6 years since its enactment, has been criticized for poor uptake among corporations that fall under its scope and a lack of adequate penalties for company non-compliance. An amended version of the Bill has recently been brought to the UK Parliament. Similarly, Australia recently launched a review of their 2018 Modern Slavery Act. Analyses of the impacts of similar, non-preventative pieces of legislation across Europe also show minimal progress towards effectively stemming modern slavery in the global supply chain.

While the efficacy of modern slavery laws has recently come into question, France in particular has set the standard for best practice in modern anti-slavery legislation with its “failure to prevent” enforcement model that emphasizes the proactive prevention of modern slavery in supply chains, rather than a given company’s willingness to report it. It’s with this in mind that the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence proposal (CSDD) requires companies to proactively identify, prevent, remedy and report on human rights abuses. In the coming years, all EU countries will be obliged to adopt it as domestic law. That being said, the EU proposal is limited in scope to “established business relationships” along the supply chain, which, for some, undermines the capacity of the legislation to protect vulnerable workers in the first mile.

Covid-19 has accelerated the shift from analog to digital auditing methods and changed the face of the transparent workplace. While the technological capabilities for improving human rights in global supply chains are growing, legislators are hesitant to apply an overly prescriptive approach to HRDD. On the other hand, there still remains a significant gap between what companies could be doing to protect workers in their supply chains, and what they’re required to do by law.

Bill S-211 will place increased reporting requirements on businesses and the Government, but it does not include new enforcement mechanisms, nor does it apply mandatory due diligence requirements such as those applied in France, the Netherlands, Germany, and that are currently under discussion at the EU level. Accordingly, Senator Julie Miville-Dechêne, sponsor of the Bill, conceded that the Bill would not “end forced labor in a single stroke,” but rather that it was a “step in the right direction.”