The following travel blog captures key learnings from our site visit to La Pampa in Madre de Dios, one of Peru’s largest illegal mining sites nestled deep in the Amazonian jungle. Ulula was recently selected as a finalist for the Partnership for Freedom’s Rethinking Supply Chains Challenge, taking our team on a journey to test our assumptions and collaborate with local actors to validate our proposed technological solutions that could equip local organizations with tools to assist their fight against human trafficking in the Peruvian illegal gold supply chain.

The tension is almost audible as we near kilometer 108 on the carretera Interoceánica; a watchman picks up his phones to announce our arrival and a local shopkeeper tells us that we should not attempt to venture in further. “Is she an undercover cop?” asks a woman working inside a small gold processing shack, my Argentinean accent not escaping her trained ear. There had already been a few robberies earlier in the morning, as many miners pack up their operations and move to the next mining site, fearful of the possibility of another police raid in La Pampa – the last being prompted by the disappearance of a Lima-born woman. With pockets full of gold nuggets, defenseless miners are the perfect target for those equipped with weaponry.

|

|

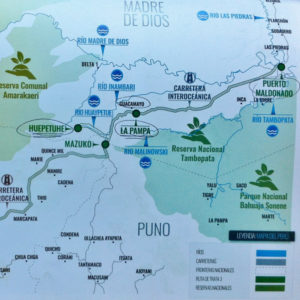

The Interoceánica is the first and only paved road connecting this remote Amazonian region to the rest of Peru. Before its construction, a car trip from Cusco to Puerto Maldonado could take as long as two weeks during the rainy season. While the extended infrastructure provided a safer and faster way to enter deep into Peru’s southeastern jungles, it brought with it the unanticipated “gold rush” that paved the way to a decade of deforestation and labour exploitation in this remote part of the country where the state is as absent as the Bald Uakari – an Amazonian monkey species at the brink of extinction.

64% of Peru’s economic activity occurs outside of state regulations, comprising the largest informal sector driven economy in South America. While the informal sector provides opportunities for subsistence to most of Peru’s poorest and most marginalized, it creates great vulnerabilities for illegal operations, systemic corruption and forced labour.

With an increase of 400% in the price of gold in the last decade, gold mining has become more profitable than the illicit cocaine trade in Peru. This explains why hundreds of thousands of young Peruvians, many of them with few job prospects in their hometowns, flock to the gold hubs in the jungle, like Madre de Dios – the epicentre of illegal gold mining in Peru. The expansion of illegal gold mining has placed Peru as the world’s second largest producer of illegal gold worldwide, second only to China, with an estimated 28% of all exported gold produced illegally and valued at US$3.3 billion per year.

This is a lot of lost tax revenue, but the government’s plan to formalize miners is failing badly. With less than 0.1% of miners formalized so far, critics say high barriers to formalization are to blame – the process of registering a business is deemed too lengthy and too costly. According to the Liberty and Democracy Institute, it takes an average of 3.5 years for a miner to pass the six stages of formalization, and it could cost as much as US$80,000. While registering a business costs money everywhere, this is a lot of money for informal miners whose monthly earnings range from US$280 to US$1,000, and who are excluded from any financial services and government support available to entrepreneurs in the formal economy.

With high barriers to register a formal business and the state largely absent from illegal mining grounds, miners, gold processors and owners of the service industries serving the residents of the temporary mining towns erected across the jungle operate in a context fertile for an activity that thrives in lawlessness – the trafficking of labour. The Interoceánica is lined with hostels, restaurants, and bars employing thousands of young women; some walk in and out freely, some are forced in, some come under false or misleading work contracts, some run away, and some suffer an even worse fate.

A local human rights lawyer tells me that the bodies of young girls are found on the side of the road almost daily, their families oftentimes completely unaware of their whereabouts. “The authorities struggle to track down the prostibars owners as they oftentimes change their names and locations, or the police are fearful to enter or are simply paid not to.” A few kilometers outside of La Pampa we see a police patrol car parked on the side of the road. “They sit there all day so they can say they had done their day’s duty, but they are too scared to enter” says our taxi driver.

|

|

According to Alternative Social Human Capital – an NGO working to uncover and stop human trafficking in Peru – one of Peru’s largest human trafficking routes ends in the mining sites of Madre de Dios. They identify the source of labour coming predominantly from underdeveloped small Andean towns in the Cusco region, where poverty rates can be as high as 75%. Lack of jobs for young people, coupled with little awareness about misleading recruitment, brings more than 2,000 mostly underage girls into the brothels inside the Madre de Dios mining sites.

While critics blame the government’s inability or unwillingness to enforce the rule of law for the rampant expansion of illegal mining in the area, attention to the issue is certainly not lacking. Environmental agencies, human rights groups, religious organizations, the local Ombudsman’s office, and other state actors like the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Peoples in Puerto Maldonado, are well aware of the expansion and complexity of illegal mining and human trafficking in the area. While the problem is gaining visibility and more attention from policymakers in Lima, it is the scope and depth of it that are unknown, preventing actors to secure enough momentum and resources to push for an adequate national response.

Unable to get near the mining sites in fear for his life, the local ombudsman shares: “We do not understand the gravity of the problem, nor can we file a formal complaint with the police if we do not have proper first-hand and reliable information”. As he shows me a hand-written list of names of potential traffickers that an informant inside La Pampa collected at great risk to his life, the ombudsman seems defeated by the enormity and obscurity of the issue. However, together with 30 other organizations dedicated to fighting the environmental degradation and human rights abuses inside of the mining sites – in what they termed the Multi Sectoral Commission against Human Trafficking – he is hopeful that they can raise the profile of the problem and receive more support from the government to assist the persons working in dire conditions or held against their will.

With over 100% mobile penetration rate and 18.5 million unique mobile users even in Peru’s most remote regions, there exists a great opportunity to leverage simple mobile technologies to shed light on the hidden criminal activities of illegal mining. While the problem extends beyond visibility and requires greater resources and oversight, providing a safe and reliable communication channel for victims can help those advocating on their behalf to gain more accurate and current insight into the victim’s’ situation so they can respond quickly and adequately. Local stakeholders supporting victims of trafficking affirmed that simple mobile channels like SMS or USSD could provide a safer and more accessible communication necessary to measure the impact of trafficking in the region and connect victims to the help they so desperately need.